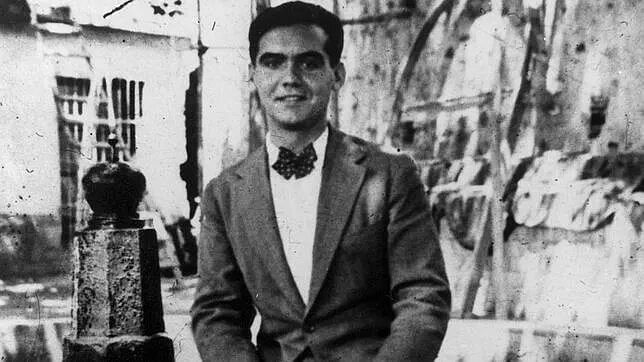

In the heart of Federico García Lorca Park, surrounded by gardens, fruit trees and the ever-present scent of jasmine, we come across Huerta de San Vicente, a museum-home that opened its doors in 1995 as a tribute to the most universal poet of the Generation of ’27. As the former holiday residence of the García Lorca family, it features many original pieces and the same layout as when the writer spent long summers between 1926 and 1936. This is a magical place where his memories live on. The baby grand piano on which the poet composed musical pieces for his nieces and nephews, an old gramophone and the desk in his room, where he wrote and corrected mature works such as Romancero Gitano (1928) and Bodas de Sangre (1932), fill the space with a timeless and melancholic air. On the afternoon of 9 August 1936, García Lorca hastily left Huerta de San Vicente in an attempt to find safe haven following the hostilities by the Civil Guard at the home of the Rosales family (friends with Falangist ties). A few days later, he was detained and executed by firearm at the Víznar Gorge, located on the outskirts of Granada.

Federico García Lorca Park, the starting point of a stroll inspired by Lorca

Take Paseo de los Tilos, which begins by the park’s main entrance on Calle Arabial, to make your way into this 71,500 m2 area around Huerta de San Vicente, the former summer residence of the García Lorca family. The home was purchased by the Granada City Council in 1985, marking the start of this tribute to the poet, and it officially opened 10 years later.

Although Paseo de los Tilos provides direct access to the large house, an option is to leave the main path and explore some of the park’s treasures, which include Neoplasticism-inspired gardens, orchards and irrigation canals, a pond and one of the largest rose gardens in Europe. The old home is the undisputed star of the space, which was developed around the 19,000 m2 summer residence that Federico García, the poet’s father, purchased in 1925. Although there are property records dating back to the 17th and 19th centuries for the orchard, which was registered by other owners—Los Marmolillos and Los Mudos—, the García Lorca family would later name it Huerta de San Vicente in honour of their matriarch, Vicenta Lorca.

As you move towards the building, the ‘prodigious’ scent of jasmine plants and many other flowers will fill the air, as Lorca mentioned in several letters he wrote to friends whilst staying in the home. ‘There are so many jasmine and Lady of the Night flowers that by sunrise we all have a tremendous headache’, he wrote to Jorge Guillén in 1926.

The museum-home: Time stopped in 1936

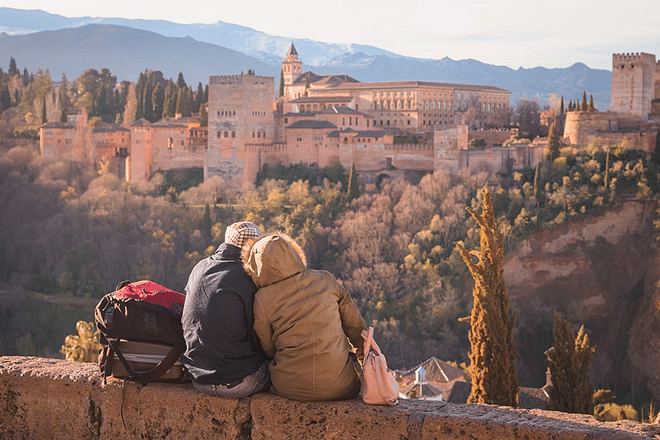

The main building façade remains unchanged from the years when the García Lorca family would place deck chairs outside to enjoy the cool summer nights. Although the door and wooden shutters were already green at the time, this feature is not evident in black and white photographs of the property. The balconies at one time boasted views of the Albaicín quarter, the Alhambra and Sierra Nevada, but this is no longer the case since new buildings now stand in the way. A 30-minute guided tour, available Tuesday through Sunday, takes us through the rooms to a world that abruptly fell apart with García Lorca’s assassination in 1936. The family, which would not spend any more summers here, ultimately emigrated to the United States in 1942.

When the Granada City Council purchased the home in 1985, the only clues of the original objects and layout of that era were obtained from photographs taken by the writer Eduardo Blanco-Amor during a visit in 1935 and from images of other places where the García Lorca lived, in which certain pieces of furniture and decorative elements were shown. Although the overall appearance today is very similar to what the poet would have seen, the Huerta de San Vicente Municipal Board of Trustees has clearly identified the original objects from other items included to recreate the past era.

For example, the mirror with an art deco frame in the sitting room is an original, as confirmed by an old photo of Federico García Lorca and his mother. The original rocking chairs and Thonet chairs are items that any reputable antiques dealer would give anything to have. The adjacent room still houses the piano that accompanied the poet—who in his youth wanted to be a musician—on countless afternoons. His old gramophone is also there: ‘Federico played many classical music records, particularly Bach and Mozart, in addition to cante jondo flamenco. […] If he did not request silence, then we also endured his insistence on listening to the same music over and over’, recalled his younger sister, Isabel García Lorca, in her memoir Recuerdos míos, published in 2002.

[experiencia id=”3451″ formato=”h”]

The upper level, where the bathroom and bedrooms of Lorca’s parents and siblings were once located, is now an exhibit hall that, in addition to hosting temporary exhibitions, also features a permanent display of original photos, drawings and manuscripts by the poet. At the back, Federico García Lorca’s room remains intact with its simple layout: a bed, a balcony, a poster of the theatre group La Barraca—with whom he travelled all over Spain performing classical works during the Second Republic—, and the same desk where his imagination flourished during so many summers. ‘[At night,] Federico would not sleep. He would open his balcony, raise the blinds and write until the sun came up. He would then close the balcony and go to bed’, explained his sister Isabel in her memoir. ‘When he went out, I would go into his room and read what he had written. I was always taken aback and felt a great deal of admiration, and he would walk in and ask, “Do you like it?”, to which I would reply, “Yes, but I don’t know why”, and he would say, “It will do, just as you may like a painting, a piece of music or a landscape”. He would open his penetrating eyes wide and remain very serious.’