‘Stat Crux dum volvitur orbis’ (The cross stands steady while the world turns). The motto of the Carthusian Order seems to summarise the more than 300 years that Carthusian monks spent religiously building the Royal Monastery of La Cartuja of Granada on the outskirts of the city. Many years passed since construction on this monastery began in 1513, which invites visitors to follow the evolution of the artistic styles that influenced European architecture during that lengthy period as they take in the solitary Carthusian lifestyle. One of the highlights is the monastery’s sacristy, a perfect example of the Spanish Baroque style. In 1835, in light of the Ecclesiastical Confiscation of Mendizábal, the religious order was forced to abandon the building. This marked the start of a period of the monument’s decline that was only halted when it received historic-artistic protection in 1932. Since the 1970s, the monastery has solemnly presided over the University Campus of Cartuja.

Three centuries of work to build La Cartuja Monastery

According to legend, during the Granada War (1482-1492), the famous Spanish soldier Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, known as the Great Captain, was about to fall victim to a Nasrid ambush at Pago de Aynadamar, a historic Moorish summer estate just north of the city and famous for its vast amount of water and fruit trees. His life was miraculously saved, so on that day, the Great Captain made a promise to build a monastery where he and his wife would be buried as a sign of their appreciation to God. As luck would have it, the Carthusian monks at the Paular Monastery in the Madrid region of Rascafría were in search of a site in Granada for their new monastery. The Order found a committed protector in the Great Captain, who was willing to donate the land and cover the costs. Work began in 1513 on what is considered to be a unique jewel of Spanish Baroque: the Royal Monastery of La Cartuja of Granada.

Despite the project’s epic launch, the following year the Carthusian monks switched to a new location a few hundred metres south due to the complicated orography and the danger posed by the suburban setting. This resulted in the Great Captain withdrawing the funding he had promised and, in turn, he was not buried at the monastery following his death.

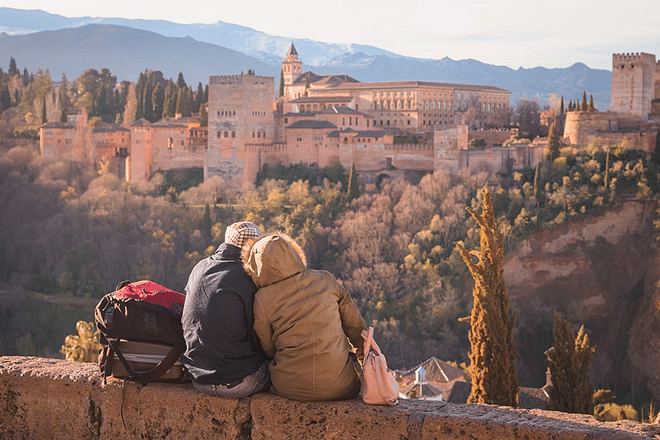

During the three centuries of its construction, the styles of various eras were included in the design of La Cartuja Monastery. As a result, the monastery features harmoniously intermingled spaces that correspond to Late Gothic, Renaissance architecture, Late Spanish Baroque and Early Neoclassicism. Perhaps in search of the solitude that defines Carthusian monks through the vow of silence they take upon entering the Order, the monastery was built on the outskirts of Granada, far from its bustling activity. The decision was made in the early 16th century and marked a new approach in choosing the location of monasteries.

The sacristy, a must-see

A well-preserved plateresque façade dating back to the 16th century welcomes us along the western side of the monastery, leading us to a Granada-style cobblestone courtyard we cross to reach the church door. This marks the start of the tour: a journey through a set of rooms that have withstood the test of time. Construction on the church began in the mid-16th century and one of the oldest spaces inside the building has a rich Baroque style. This spot, which connects to all the other rooms, is the starting point of our tour. On one side is the cloister, which was built in the mid-17th century as an inner courtyard surrounded by a number of chapels. These chapels are now used to display the vast artistic collection left behind by the famous Carthusian friar Juan Sánchez Cotán. Two themed groups of paintings catch our eye: one on the origin and early days of the Order and the other on the martyrdoms of the Carthusian priors in the England of Henry VIII.

Another room to be viewed is the sancta sanctorum, which only connects to the church. Built between 1704 and 1720 behind the high altar, this small room is hidden behind a Venetian glass door and was used to store the sacramental bread used during mass. Upon entering, we come across an impressive red and black marble tabernacle that houses the Eucharist. Other elements that stand out are the room’s exaggerated ornaments and the magnificent dome with paintings of Saint Bruno, the founder of the Carthusian Order, as he literally carries the world on his shoulders.

Returning to the church, we must make a stop at the sacristy, the jewel of La Cartuja of Granada. Built over a 37-year period, this immaculate room seems larger than it actually is due to the vast decoration and wide array of colours used. The main altar at the far end stands out along with a statue of Saint Bruno made by the sculptor José de Mora and considered by many as the masterpiece of Spanish Baroque.

The years since the departure of the Carthusians

The Ecclesiastical Confiscation of Mendizábal marked the definitive secularization of Carthusian monks in 1835 and the sale of the monastic complex. Since then, a number of demolitions have been carried out that affected the great cloister and the priory residence, among other elements, and we only know of their existence today thanks to the historic blueprints of the monastery. At the end of the 19th century, Compañía de Jesús acquired the land and in 1932, the monastery received historic-artistic protection, thereby ending its unjust decline.

Throughout these 150 years of Carthusian absence, the monastery has silently observed its changing surroundings. Although in the 16th century it was tucked away in the solitary outskirts of Granada, today it has a cheerful companion in the form of the University Campus of Cartuja. In 2017, a group of professors requested to have the entire area declared a Heritage Site, a legal protection that is justified by the region’s rich landscape and variety of archaeological sites. Along the hill, it is worth noting the existence of excavated dating back to the Neolithic period and the remains of a Roman potter’s workshop in which ten ancient kilns have been found.