Nestled between Calle Real de Cartuja, Calle Ancha de Capuchinos and Cuesta del Hospicio, and overlooking the Triunfo Gardens that at one point were the site of Islamic tombs, we come across the Royal Hospital of Granada. The Catholic Monarchs ordered the construction of this facility in 1504 as part of the effort to renovate the image of the recently-conquered city, and the city’s new Christian residents did not take long to become accustomed to the presence of syphilis patients and the mentally ill inside the building. However, the beds and surgical equipment were removed from this regal building many years ago. In their place, the Royal Hospital has housed the Vice-Chancellor’s Office of the University of Granada along with its prestigious main library since 1981. The extraordinarily overlapping architectural styles—primarily Renaissance—included in the building throughout the lengthy duration of its construction are reason enough for a visit. Additionally, thanks to an initiative by the Hospitaller Order of the Brothers of Saint John of God, the interior still contains the cell in which the Portuguese saint lived as a recluse for a year and where he continues to be revered.

History and symbolism around the creation of the Royal Hospital of Granada

The Royal Hospital of Granada is one of the many institutional buildings that the Catholic Monarchs had built after the city was retaken in 1492 in an effort to redefine an area that had remained under Moorish rule for eight centuries. Since at the time Granada was lacking an official place for healing, it was decided that, in what could be viewed as a symbolic event, the new facility would be built on the site of the former Muslim cemetery Saad Malik, near the historic Puerta de Elvira gate. Ironically, a similar building was erected on what is today the Triunfo Gardens, directly in front of the hospital. It is said that in the 18th century, this spot, which commemorates the Immaculate Conception with a monumental column in the middle, was the site of festivals and celebrations before becoming a place of public execution following the French occupation, with Mariana Pineda, the ‘heroine of liberty’, as the most famous victim.

An heir of Milan’s Ospedale Maggiore Renaissance style that became popular throughout Europe as of the 16th century, the Royal Hospital began treating patients from the Granada War before the original facility was even completed. These soldiers were followed by poor people, pilgrims, syphilis patients and even, as documented in books, those referred to as ‘inocentes’ (the mentally ill) after work on the facility was sped up with support from Charles V in 1522 upon the death of his grandfather Ferdinand II.

A tour of the building

Walking up Cuesta del Hospicio and leaving behind a fence that originally belonged to what used to be San Lázaro Hospital, we reach the main entrance of the Royal Hospital. From this street, visitors can begin noticing the magnificent repertoire of plateresque windows on the main façade in addition to the extraordinary Baroque doorway, built using stones from the Sierra Elvira mountains, that Alonso de Mena created in 1640 and features allegorical carvings such as those of the yoke and arrows in honour of Isabella I and Ferdinand II.

Although the hospital design is clearly a reproduction of Filarete’s innovative work in Milan as the Renaissance emerged, the version in Granada incorporates unique features. Perhaps due to the long duration of its construction or the historic crossroads it represents, visiting the Royal Hospital is more pleasant if attention is paid to how certain Renaissance elements, such as the columns in the Marble Courtyard, are harmoniously intertwined with characteristic Gothic elements, like the cupola of the lantern tower or the Mudejar-style structures. Featuring a cross-shaped layout, the hospital has four symmetrical courtyards with histories that are closely linked to their original purposes.

For example, the Marble Patio, located on the left upon entering the building, has 20 arches supported by Corinthian columns and hides an interesting fact. If we search for initials carved into the arches, we can find an F for Ferdinand and a K for Charles V, although the latter was originally a Y for Isabella I but the emperor altered it to include his personal stamp.

As we continue, on the left we come across the Chapel Courtyard, which is supposedly the only courtyard whose decorative work was officially completed. It was named after an old chapel that no longer exists but formerly contained the remains of the shackles used to restrain the Portuguese Saint John of God, who had been locked up because he was thought to be crazy.

The Innocents Courtyard and the Archive Courtyard were originally undefined, so their appearance is barer than the others, although they house interesting details. For example, the Innocents Courtyard offers a view of the small window to the cell where the aforementioned saint was held. This cell now houses the Sanjuanista library, a place of knowledge with books about the humanitarian work carried out by Saint John of God, such as when he supposedly saved several hospital patients during a major fire in 1549. The scene was depicted in a painting by the artist Gómez-Moreno around 1880.

The Royal Hospital today

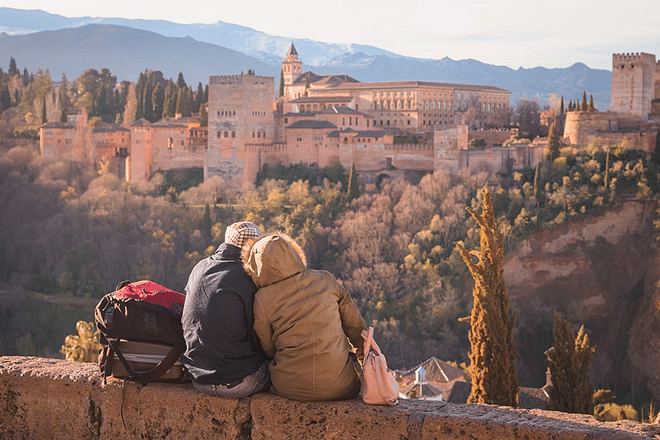

At night, the dancing fountains in the Triunfo Garden light up with plastic colours, seemingly unaware of the age-old witness with a serious expression that stands behind them. In the mornings, university pupils can be seen crossing the front entrance, immersed in academic activities or reading books in the main library on the second floor.

When it underwent numerous restorations in the 1960s and 1970s, the Royal Hospital of Granada watched as the old structures attached to its perimeter were demolished and a great garden, with more than 360 tree species, was built around it. Despite its new academic purpose, the building continues to attract visitors interested in the historical essence exuded by its former use. Additionally, the courtyards have served as the venue for an array of cultural events, including all types of exhibitions and concerts, for many years.