Granada would be nothing without Albaicín. The city was founded in this Arab quarter built around Alcazaba Cadima, which the Zirid dynasty started constructing in 1013 on a hill bathed by the Darro River. This is how Muslim Granada—Medina Garnata—came to be, and at its peak it became the capital of the Nasrid kingdom in the 15th century. Today, that urban maze lives on in an intricate labyrinth of narrow streets filled with old tales, but the quarter has evolved into an eclectic identity in which the ancient doors, traditional water tanks and Arab baths coexist with Christian churches—most built on former mosques—and Renaissance buildings. For these and many other reasons, it has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1984. These two strolls—one on flat land along the river and the other upwards to the lookouts—are a journey to a place that has always been its own universe. Although the quarter forms part of the city, when Albaicín residents go to the city centre, they say, ‘I’m going to make my way down to Granada’.

Related experiences

The treasures of the riverbank along the Darro

Our route begins at Plaza Nueva in front of the Royal Chancellery (Real Chancillería), the first building constructed in 1531 to house a court of justice. The Candle Tower can be seen over the rooftops because the Alhambra is nearby, on Sabika Hill across the Darro River. On the far end of the square, towards Carrera del Darro, we can see the first example of a phenomenon that is present throughout Albaicín: the Church of Santa Ana, built in 1537—based on blueprints from the great Renaissance architect Diego de Siloé—where the Almanzora mosque was originally located.

Continuing along the river, it is a delight to gaze at the watercourse and lush vegetation from one of the stone bridges that cross it. The El Bañuelo Arab baths are located nearby. Dating back to the era of the 11th century Zirid King Badis, the famous water baths crowned with star-shaped skylights can be visited for free. Directly across the river, the ruins of the ancient Cadí Bridge that connected Alcazaba Cadima with the Alhambra now serve as a dam.

The Darro takes us to the Renaissance Castril Palace, which currently houses the Granada Archaeology Museum featuring a beautiful plateresque façade and coffered ceilings. The words ‘Esperándola del cielo’ (Waiting for her from heaven) can be seen above a walled balcony. This carving refers to an old legend involving the grandson of Hernando de Zafra, the royal secretary of the Catholic Monarchs. Following the conquest, he was rewarded with permission to build this palace facing the Alhambra.

For centuries it has been said that Zafra hung a servant who had walked in on his daughter as she was partly undressed. Before dying, the servant asked for divine justice since in reality he had walked in on the actual lover, who escaped through the balcony. Without mercy, Zafra replied, ‘Hung you will be, waiting for her from heaven’. Following the execution, he had the balcony bricked up and the famous words carved into the wall as a warning to potential suitors of his daughter, who ultimately killed herself. According to legend, the day that Zafra died in 1600, a great storm caused the Darro Rive to overflow, dragging his coffin downstream as divine punishment as it was being taken to the cemetery. For this reason, when Granada experiences heavy rains, people still say that ‘It is raining more than when Zafra was buried’.

Our walk ends at the famous Paseo de los Tristes, as people refer to it—although the official name on maps is Paseo del Padre Manjón—, because funeral processions on the way to Granada’s San José cemetery on Sabika Hill once passed through here. This lovely spot is always busy and also a great place to eat local tapas at one of the many bars whilst taking in views of the Alhambra.

[experiencia id=”3519″ formato=”h”]

Making our way up to Albaicín

The route to the top of Albaicín begins at Puerta de Elvira, a spot below the hill that explains Granada’s roots. As of the 11th century, this great arch served as the traditional entrance to Albaicín from the nearby Medina Elvira, which was an important city between the 7th and 11th centuries until Medina Garnata was built. This marks the start of Cuesta de Alhacaba, a steep slope leading to the labyrinth of narrow streets and cármenes, traditional Granada villas with gardens featuring ivy and vines that fill the air with the scent of jasmine.

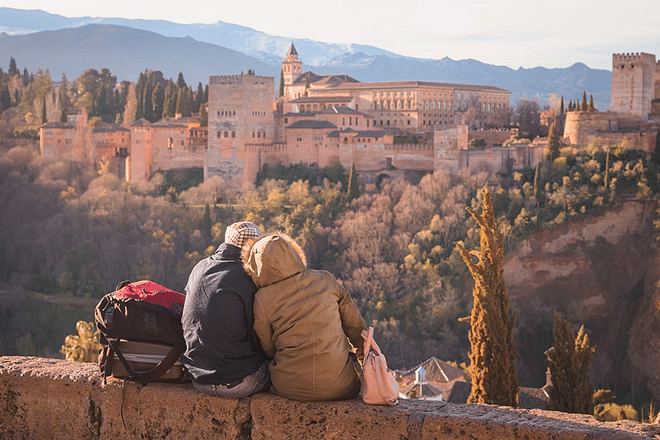

After a 1.5 km uphill climb, we finally reach the heart of Albaicín Alto, the lively Plaza Larga filled with bars and Middle Eastern pastry shops that is always bustling. Next to it, a stretch of the 11th century wall that separated the Albaicín quarter from the interior of Alcazaba Cadima—that no longer exists—, opens up to Arco de las Pesas, which owes its name to the rigged scales that were hung after being seized by authorities from merchants who cheated their customers. Crossing the arch, the narrow San Cecilio street will quickly take us to Mirador de San Nicolás. This scenic overlook is a required stop and a place in which to listen to flamenco street musicians whilst enjoying the sunset and the breathtaking views of the Alhambra and Granada, with Sierra Nevada as the backdrop. The modern Great Mosque of Granada is only a few metres away. It was inaugurated in 2003 following a 511-year period (since 1492) in which no other Muslim temples were built in the city.

Heading back to the lower part of Albaicín, we can cross Placeta del Cristo de las Azucenas. Like many other streets in the neighbourhood, its name is linked to a legend. It is said that the aunt of an orphan, whom a suitor had dishonoured by sleeping with her, bumped into the young man in this square where someone had placed a withered bouquet of Madonna lilies next to an image of Christ. When the woman demanded that he marry her niece, he replied that he would do so when the dried flowers came back to life. To his surprise, the Madonna lilies miraculously flowered and he was forced to marry the young orphan.

This square is also home to Aljibe del Rey, the largest traditional water tank in Albaicín that, starting in the 11th century, supplied water to the orchards of the Ziri King Badis. Turning onto Callejón de las Monjas, we come across the highlight of the cultural segment of this route: the nearby Palace of Dar Al-Horra, an excellent example of 15th century Nasrid architecture and the residence of Queen Aixa, Boabdil’s mother. According to legend, as they fled the city she told her son, ‘Do not cry as a woman for what you could not defend as a man’.

Just a few feet away, there is nothing better than food and drinks on the terrace of one of the bars or restaurants at Mirador de la Lona and Placeta de San Miguel Bajo to take in everything we have seen and learned. If you have energy to walk ten more minutes, head down Calle Cruz de Quirós to Calle Calderería Nueva, a paradise of tea shops and Middle Eastern sweets.

This humble overview covers only a tiny fraction of the treasures hidden in the steep, narrow streets of endless Albaicín, where there is only one rule: if you get lost whilst wandering through the quarter, simply take any road that leads downward. This is the only guaranteed way to exit the labyrinth.