Early Arabic writers referred to Granada as a crown with a tiara: the Alhambra. Centuries later, in 1829, Washington Irving, a North American Romantic writer, gave his first impressions of the monument following a long trip through Andalusia: ‘From a distance, romantic Granada could be seen, crowned by the reddish towers of the Alhambra, and above the battlements, the snow-capped peaks of Sierra Nevada glowed like silver’. Sabika Hill, located in the fertile meadow between the Darro and Genil rivers on the outskirts of the city, is one of those magnetic places that has attracted many civilisations. As the home of various defensive buildings from before the Roman era, construction on the Nasrid fortress we know today began in the 13th century to create a masterpiece of the refined art and the Al-Andalus culture that covered the Iberian peninsula during seven centuries.

The Alhambra would later become the temporary home of Christian kings—in 1526, Carlos V ordered the construction of his own Renaissance palace with which to ‘eclipse’ that of the Arab monarchs—and even of vagrants and beggars who in the 19th century occupied the abandoned palaces, which had been seriously damaged by Napoleon’s troops.

The beauty of the monuments, declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1984, inspired the poet Francisco de Asís de Icaza to write these popular words that appear on a ceramic plaque at the base of the Candle Tower: ‘Dale limosna mujer / que no hay en la vida nada / como la pena de ser / ciego en Granada’ (Give him alms, woman, for there is nothing sadder in life than being blind in Granada). This article strives to refute this statement because the gardens, palaces and legends of the Alhambra should be enjoyed with the five senses. It is a journey through the senses.

Related experiences

The 1,001 nocturnal fragrances of the Generalife Gardens

Visiting the Generalife Palace and Gardens at night is as close as you can get to stepping into the tale of One Thousand and One Nights. After the sun goes down, shadows take over this summer palace and country estate of Nasrid rulers, and the fragrances of the more than 600 plant species remind us of forgotten legends. ‘Some of these flowers can summarise the spirit of the Alhambra’, Cristóbal Romero, the head gardener of the Generalife once stated. Here, water from the Royal Canal reaches every corner of the property through fountains and sprinklers that supply moisture to the orange blossoms, jasmine plants and roses. If we follow the scents, we can reach emblematic spots inside the palace such as the Water Channel Courtyard or the Courtyard of the Sultana’s Cypress Tree. The latter owes its name to a tree that witnessed the infidelities of Morayma, the wife of King Boabdil, with a gentleman of the Abencerrajes tribe. In a corner of the property, presided by a pond surrounded by a myrtle hedge, lies the dried trunk of the old cypress tree.

The eternal song of the Water Steps

Walking up the Lion Steps that lead to the Generalife High Gardens, we come across one of the oldest and most special elements of the property: the Water Steps. According to legend, to address the elevation difference between the Palace and a small chapel at the top of the hill, the Sultan ordered the construction of these steps that feature a handrail consisting of two channels through which water from the Royal Canal flows. The eternal symphony creates a cool and relaxing atmosphere that invites visitors to stop at one of the round landings under the laurel trees along the way and close their eyes. The sound of the flowing water is the same as during the era of Abu al-Ahmar, the founder of the Alhambra.

The Nasrid Palaces, a connection to history

In the heart of the palatial city—as the citadel-fortress surrounded by walls is referred to—three of the palaces where the Nasrid rulers lived in the 14th and 15th centuries still exist: the Mexuar, the Comares Palace and the Palace of the Lions. These are not the first or the only palaces that were built—others were destroyed or reconverted by Christians—, but their good condition invites visitors to step into the era of the Nasrid kingdom at its peak, during the times of Yusuf I and his son, Mohamed V.

‘Enter and fear not ask to ask for justice, for you will find it’ can be read on a tile by the door to the Mexuar, the oldest but also the most renovated of the three and the place where the Sultan met with his ministers and dispensed justice. The Mexuar, however, is a humble precursor to the incredible and sophisticated decorative richness of the other halls and patios inside the palatial city.

With all due respect to the ominous Hall of the Ambassadors in the Tower of Comares, where King Yusuf I sat at his throne under a sublime dome representing the seven heavens of Allah, the universal symbol of the Alhambra is the Courtyard of the Lions. The famous fountain in the middle, protected by 124 columns, is an icon of the artistic height and hydraulic technical complexity that was achieved under the rule of Mohamed V. Of the halls by the courtyard that are usually filled with tourists who are dazzled by the virtuosity of the plasterwork, tiles and impressive mocárabe domes, one is the Hall of the Abencerrajes. Here, according to legend, King Boabdil ordered the leaders of this North African tribe to be killed after discovering his wife’s famous infidelity under the cypress tree.

In the 19th century, this and many other events would be documented by the writer and traveller Washington Irving, who wrote the book Tales of the Alhambra during his stay in some of the abandoned halls of the Nasrid palaces, as marked by a plaque on the wall.

The Candle Tower that sees everything

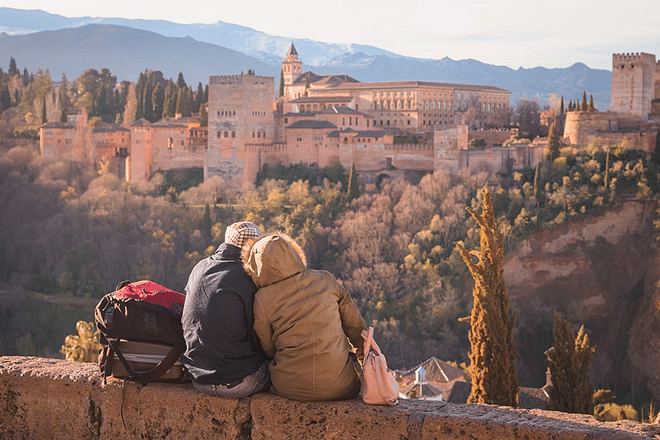

The Candle Tower is the perfect place from which to take in the surroundings because the top offers panoramic views of Granada, Sierra Nevada, Granada’s meadow and several nearby towns. Standing at 26.8 metres, this is the tallest tower of the Alcazaba, the defensive fortification around which the Alhambra was built. In fact, it is believed that Abu al-Ahmar, the founder of the location and the first Nasrid ruler, established his residence in the nearby Tower of Homage in 1238.

For centuries, the Candle Tower set the pace for the people who lived near the Alhambra with its bell, which remains up high. Muslims would ring the bell to announce ordinances and commemorations, to inform farmers of night-time watering hours or to warn of dangers and disasters. The biggest event took place on 2 January 1492, when King Boabdil handed over the key to the city to the Catholic Monarchs following a prolonged siege. To commemorate this, a tradition showcases the bell every January 2nd, when locals believe that any single ladies who touch the bell on that day will be married by the end of the year.

Spanish-Arab flavours in the heart of the Alhambra

A well-earned stop during this multisensory tour of the Alhambra can be found without leaving the walled complex at the Parador de San Francisco hotel, which offers a magnificent opportunity to stimulate the only sense that the monuments have not been able to touch: taste. The restaurant at this hotel, which forms part of Spain’s parador network, serves an array of Spanish-Arab creations that can be enjoyed on a terrace overlooking the Generalife Gardens. Granada-style remojón (bread soaked in milk), monkfish in Mozarabic sauce, Alpujarra-style kid goat and Santa Fe pionono pastries are just some of the dishes with which to savour the remarkable features of the Alhambra from a different perspective. Another interesting fact is that the hotel is housed in a historic monastery that the Catholic Monarchs ordered to be built in 1494 on top of the Nasrid palace of Los Infantes. The Catholic Monarchs were temporarily laid to rest in the monastery until 1521 and the building hosted the first mass following the Christian Reconquista of Granada on 6 January 1492. New conversation topics for after-dinner chats.