Construction on Granada’s first Christian monastery, the Monastery of San Jerónimo, began in 1504 on land that is believed to have belonged to Boabdil, the last Nasrid king. Using stones from the Moorish wall and the historic Puerta de Elvira, the new building that the Catholic Monarchs had promised to members of the Order of Saint Jerome—who resided at a nearby temple in Santa Fe since 1492—became a reality. However, the monumental building, made up of a church and two cloisters, has gone down in history as much more than this. It is the jewel of Spanish Renaissance—thanks to the work of Diego de Siloé, a renowned architect from Burgos—and also the tomb of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, the courageous Great Captain who played a key role in the surrender of the Moors and who rests next to his wife under the impressive Mannerist altar in the main chapel.

From Gothic to Renaissance: A building that defined a new era

Sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs in recognition of the Hieronymite friar Hernando de Talavera—the first primer Archbishop of Granada and a key player in the city’s Christianisation—, work on the Monastery of San Jerónimo initially followed the Gothic style that was frequently seen in monuments financed by royalty at the time. However, everything changed in 1520 when the widow of the Great Captain, María de Manrique, assumed the project’s funding in return for a spot in the church’s main chapel so she and her husband—who had died from illness in 1515—could be buried there. Two architects—first Jacobo Florentino and then Diego de Siloé as of 1526—decided to replace the Gothic style with the new Italian Renaissance model that they believed better conveyed the values of the city’s new Christian nobility. As a result, the construction of the Monastery of San Jerónimo was a turning point that marked the end of the Middle Ages and the start of the modern era, and also a light that illuminated the artistic and urbanistic destiny of Granada in the decades that followed.

The turbulent history of the Monastery of San Jerónimo

Since the Hieronymite monks set up residence here in 1521, while the Monastery of San Jerónimo was still under construction, the religious building has faced a number of challenges throughout the five centuries that have passed. For more than 300 years, the monks lived in one of the city’s most prosperous monasteries that was even expanded with the addition of courtyards, pens, stables, wine cellars and even a hostelry. Everything changed in the 19th century when the monastery was taken over by Napoleon’s troops to be used as artillery barracks. The French sacked its treasures, desecrated the Great Captain’s tomb, demolished the bell tower and used the stones to build the Puente Verde bridge over the Genil River, linking Paseo de la Bomba and Avenida de Cervantes. Things did not improve for the friars with the Ecclesiastical Confiscation of Mendizábal in 1835, when the building was repurposed into barracks and the monks were expelled until 1967, at which point the monastery was returned to the Order of Saint Jerome. Classified as a Cultural Heritage Site, it has undergone a number of restorations that included rebuilding the ill-fated tower in the 1980s. Sadly, two courtyards, the hostelry and other areas have been lost with the passing of time.

On a more positive note, two magnificent cloisters whose side chapels contain the monastic cells of monks and several chapels built by distinguished Granada families still remain. The main cloister is a large square-shaped space surrounded by two levels of side chapels, each with nine arches, around a central garden. The central arches along the sides are presided by the emblems of the Catholic Monarchs and of the friar Hernando de Talavera, and the second floor features seven arcosolia that Diego de Siloé decorated with Renaissance ornaments. The central garden has been replanted with orange trees, just as it was in the 16th century, as chronicled by Andrea Navagiero, Venetian ambassador to the court of Spain, who visited the monastery in 1526: ‘The Hieronymite monastery contains gardens, fountains and two gorgeous cloisters unlike anything I have ever seen. One is larger and more magnificent than the other, and the central area is filled with orange trees, fragrant citron trees, myrtle thicket and other exquisite plants’.

Navagiero had travelled to Granada for the wedding of Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Empress Isabella of Portugal. During her stay, the queen resided in the monastery’s second cloister, which is not open to visitors because it currently houses the enclosed order of a community of Hieronymite nuns.

Church of San Jerónimo, the tomb of the Great Captain

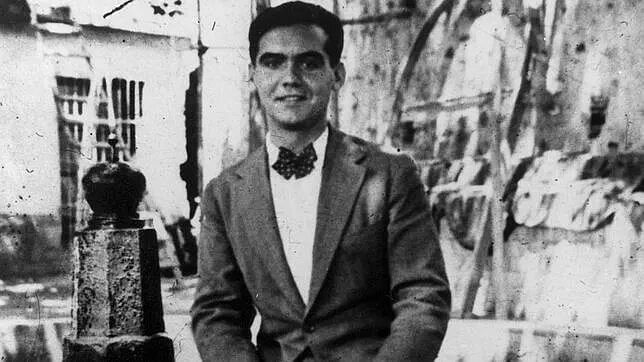

The lovely and monumental façade of the Church of San Jerónimo, a temple we primarily owe to Diego de Siloé, clearly hints at what lies within. Almost as a signature of the temple’s owner, the central wall section is presided by an emblem of the Fernández de Córdoba family that is held up by two warriors and a Latin inscription reminding us that the Great Captain was a renowned Spanish duke who terrorised the Moors. This politician and soldier, known for his military genius in the war against the Nasrid kingdom, would later become an essential diplomatic figure in the negotiations that led to the Treaty of Granada thanks to his friendship with Boabdil, the last king of the Moorish dynasty. The flanking walls contain two large medallions with depictions of the noble warrior and his wife, María de Manrique.

The most interesting elements inside are the transept and the high altar in the main chapel, a masterpiece of Spanish Renaissance and of Andalusian Mannerism. Created between 1570 and 1605 by several acclaimed sculptors, the iconography is designed to praise the military achievements and heroism of the Great Captain. On either side of the monumental altar’s base, the statues of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba and his wife stand in prayer, dressed in how they wanted to be remembered to achieve eternal glory: with him wearing armour as a victorious soldier; and her with a veil, robe and cloak, as a modest and pious woman. At the foot of the stairway of the main altar, the few remains left of the founders are located under a marble slab with the following inscription: ‘The bones of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, who with his bravery earned the title of Great Captain, lie here in this tomb until eventually they return to the everlasting light. His glory was by no means buried with him’.