Spread out between Granada’s two rivers—the Darro and the Genil—, the labyrinth of steep and narrow streets in Realejo comprises what used to be the city’s Jewish neighbourhood. Sephardi Jews had already settled here well before the arrival of the Moors in the 8th century. The new inhabitants called this district Garnata al-Yahud (Granada of the Jews) and admired the culture and cosmopolitan nature of its artisans and merchants, who tended to speak several languages and were familiar with current events from around the world thanks to their constant travels. However, the prosperity of the Jewish quarter did not last. Conflicts with the Muslims turned this area into a ghetto, and when Granada was conquered in 1492, the Catholic Monarchs ordered the expulsion of all the Sephardi Jews. The construction of new Christian buildings on the site of demolished synagogues left little trace of the Jewish era, giving today’s Realejo an eclectic and multicultural air. Despite this, its 17,000 residents are still referred to as greñúos, supposedly in reference to the curly hair of the former Sephardi residents.

A tour of Granada’s three cultures: Plaza de Isabel la Católica – Sephardic Museum – Torres Bermejas

Realejo is a neighbourhood through which a brief stroll reveals the remains of the people that have defined Granada’s history: Jews, Moors and Christians. Our route begins at Plaza de Isabel la Católica, in front of the magnificent realist statue of Christopher Columbus with the queen, who on 31 March 1492, in the Alhambra, ordered the expulsion of the Jews. Turning onto Calle Pavaneras, we will come across, ironically, the statue of Yehuda Ibn Tibon, one of Granada’s most renowned Jews. As a physician, philosopher, poet and translator, his countless translations of Arabic texts into Hebrew made it possible for Arab science to reach Europe.

To the left of the wise Jew is another building that quietly shares Granada’s history with us: the Monastery of San Francisco. Built in 1507 on the site of a former mosque, the Alhambra Franciscans decided to relocate here when the Realejo district became a ghost town following the expulsion of the Jews. The city’s first archbishop, Friar Hernando de Talavera, is buried here. The monastery, of which only an imperial staircase and a 16th century cloister with a central fountain and a well remain, now houses the headquarters of the Training & Indoctrination Command (known by its Spanish acronym, MADOC).

Continuing along Calle Pavaneras, on the left stands the famous Casa de los Tiros, which owes its name to the artillery weapons that peer out of the battlements. The building looks like a military fortress and dates back to the 16th century, although the impressive tower on the outer façade is the only original element that remains. Casa de los Tiros is now the city’s history museum, which has an excellent library and newspaper archive. It was first owned by the Granada-Venegas family, an interesting lineage of noble Muslim converts who, following the conquest of Granada, renounced their roots to establish a closer relationship with Castilla, thereby becoming perhaps the most reactionary individuals against the Moors. The family became so thoroughly integrated that in 1643, Philip IV of Spain gave them, in return for their service to the Crown, the rank of Marquis of Campotéjar, which included ownership of Casa de los Tiros and the Generalife gardens until 1921, when they were transferred to the state following a drawn-out legal battle. The family motto, ‘El corazón manda’ (The heart rules), can be read above the door of Casa de los Tiros.

At this point, to gain a better understanding of the legacy of Garnata al-Yahud, turn left to reach the Sephardic Museum. This small building is run by a Jewish family and its aim is to remind visitors that well before the Muslims and Christians arrived, the Jews were already in Granada—the first mention dates back to the year 303—, until their expulsion in 1492. If we continue along this uphill street, we suggest taking a break at Placeta Puerta del Sol, a square with a lovely 17th century fountain for washing that is also one of the city’s lookout points.

Heading back to Casa de los Tiros, we continue walking down the street (which is no longer called Calle Pavaneras and is now Calle Santa Escolástica) to Plaza del Realejo. The Church of Santo Domingo is just a stone’s throw away. This historic temple that combines Gothic, Renaissance and Baroque styles is where the sessions of the Tribunal of the Holy Inquisition were held and also the burial site of various Granada nobles.

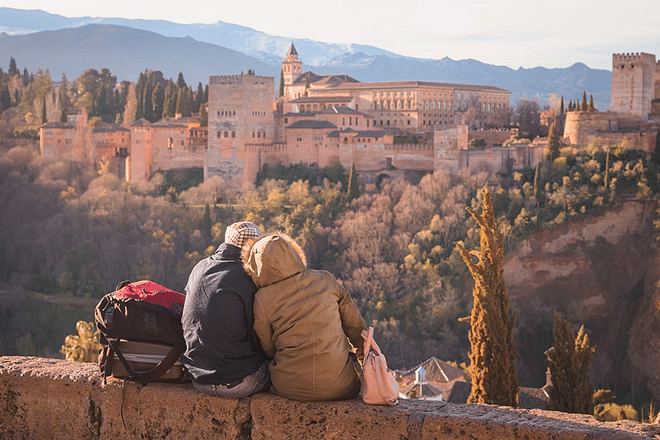

Following this short detour, it is time to climb Cuesta del Realejo, a steep street with steps, as seen in many Jewish quarters, that connected the lower and upper areas of the Realejo district. Once we reach the top of Mauror Hill and are out of breath, we turn left onto Calle Aire Alta, which will take us directly to the mysterious Torres Bermejas. Although their exact date of construction is not known, these watchtowers formed part of a fortified defensive bastion that was connected by a wall to Granada’s Alcazaba, from which there are lovely views. Although certain researchers attribute it to Ibn Al-Ahmar, the person who founded the Alhambra in the 13th century, others believe that the Torres Bermejas may have been built as early as in the 11th century.

Two emblematic streets at the top of Mauror Hill, Callejón del Niño del Royo and Calle Antequeruela Alta—reminding us that this district took in the Moorish residents of Antequera when it was recaptured by the Christians in 1410—, are home to two of Granada’s most beautiful cármenes (traditional villas with gardens). They are the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation and Carmen de los Mártires, two magical places that, due to their vast wealth and history, we will explain in greater detail in separate articles.

Campo del Príncipe, the heart of the Realejo quarter

Heading down Calle Antequeruela Baja, we reach Campo del Príncipe, the heart of the Realejo district. It has been the location for all types of public events and celebrations since Nasrid times, when it was known as Campo de la Loma. In 1497, the Catholic Monarchs widened the square and named it after the recent marriage of their son John, Prince of Asturias, with Margaret of Austria.

Upon entering the square, we can see the Church of San Cecilio, which features a beautiful plateresque façade and was built in the 16th century on the site of a former synagogue. Directly across is the renowned Cristo de los Favores (Christ of Favours), a jasper and alabaster statue that has stood at this spot since 1682. It was built in 1640 with donations from nearby residents and has since served as an object of devotion for the local greñúos. Those who are lucky enough to be here at three in the afternoon on Good Friday can join the crowd that comes together around the crucified Christ because this is when, according to legend, he grants three wishes to everyone who makes them. The recurrence of the number three is no coincidence: Jesus died at the Ninth Hour, which is three in the afternoon, and the local greñúos believe that the statue depicts Christ three minutes before his death.