In 1915, following the start of World War I, José María Rodríguez-Acosta, a painter from Granada, set his brushes aside to focus all of his efforts on the construction of a carmen villa in which to establish his studio. As the son of a family of bankers, his comfortable financial situation made it possible for work to continue until 1930, transforming the building and its gardens into a reflection of the ivory tower in which he had always lived, an artistic creation that integrated the mysteries of the East with the Greco-Latin rationality of the West and melded with Granada’s timeless landscapes. The idea progressively took shape in his head until it became a vital project that came to life following his death in 1941. That same year, as instructed in his will, the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation was founded at this extraordinary spot atop Mauror Hill, near the Alhambra and Torres Bermejas. Its aim was to ‘keep Granada up to date on all the knowledge of human progress and serve as a stimulus for people of an elevated spirit’. Today, his posthumous wish has become a reality: the foundation is one of the city’s cultural backbones thanks to its wide array of artistic and archaeological collections, library and archive, and extensive educational programme featuring tours and student workshops.

The White Carmen, a rare architectural beauty

Perched on Mauror Hill, directly below the Alhambra that crowns the summit, it is surprising to see this discrete white building with several towers that seem to imitate those of a Nasrid fortress, although with a contemporary style. As many as four architects contributed to the construction of this architectural rarity that was declared a national monument in 1982. It combines a cubist and functional style that was typical of 1920s avant-garde with the Andalusian regionalism of Granada’s carmenes, and includes historic elements from Renaissance, Baroque and Hispano-Arabic styles.

The eclectic interior decor gives us an idea of the painter’s refined and cosmopolitan taste, and the rooms are filled with all types of historic-artistic objects. Many of these items were acquired on his trips around the world, including Buddha busts and many other pieces of Asian art, ivory creations, Persian rugs, sculptures, jewels, Greco-Roman and Iberian artworks, and even one of the first film projectors from the 20th century.

The highlight of the tour is the painter’s study and library, featuring an unexpected art deco medley that contrasts with the discrete exterior. Some of the works by Rodríguez-Acosta, who was an example of modernism and symbolism in Spain, are hung on the walls. The study contains an unfinished painting that the artist was working on when he died from a sudden illness at the age of 62. The nude piece of a sleeping woman is filled with symbolism, just like most of the works painted by the artist in his final years. Some experts believe that this painting is the artist’s masterpiece as he tried to express, towards the end of his life, the eternal struggle between the body and the spirit. The fact that it is unfinished reminds us of who won the battle.

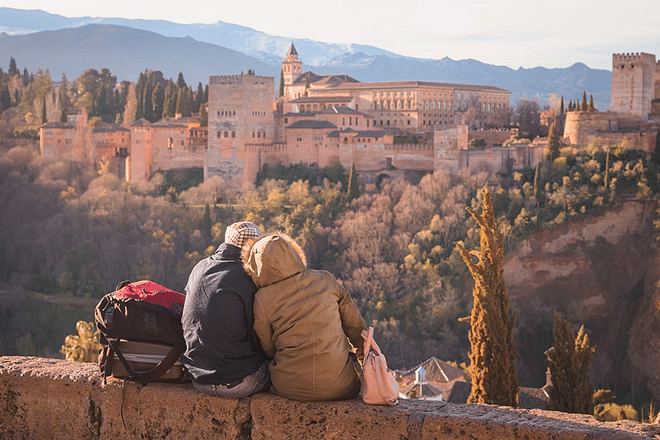

The gardens at the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation, an eclectic and subjective experience

The villa’s gardens on the hillside are comprised by a series of terraces and lookout points at different heights that boast breathtaking views of Granada. This vertical structure makes it possible for each terrace to be seen from several perspectives (from above, from below and at the same level), and combined with the eclectic and symbolist monumental decor, the garden is a work of art in and of itself. A stroll through this space is a subjective experience of discovery filled with suggestions.

The art historian and former mayor of Granada Antonio Gallego Burín described it as follows: ‘The gardens of the carmen are connected to each other by means of uneven steps that are traditional of Muslim architecture. The trees, cypresses and plants are intertwined through pictorial logic with the architectural elements, colonnades, gazebos, pergolas, fountains and statues, in which the visual perspectives and the landscape are the axis of the composition that melds classic and Muslim worlds’.

Spread out along the four gardens, a number of historical artworks of various origins can be found: columns dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries, Gothic lintels, Islamic columns and capitals, a Roman statue of Apollo, a Renaissance baptismal font and more.The sculptor Pablo de Loyzaga completed the decor by adding copies of low reliefs and classic sculptures. Although it may not be evident at first sight, all of these elements quietly converse with each other because the garden was designed in accordance with a symbolic iconography centred around great human themes such as love, death, ruin, insanity and contemplative life.

However, the biggest mystery of the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation’s gardens is hidden below ground, where a maze of subterranean galleries make their way across the hill. Although many already existed before the carmen was built, the painter extended them and decorated the nooks with sculptures that create a romantic, ghostly atmosphere. A tour of the carmen should always include this hidden treasure.

Showcasing the foundation: its educational programme

The earliest members of the foundation’s board of trustees, which included renowned individuals such as José Ortega y Gasset, Fernando de los Ríos and Manuel de Falla, had one request from Rodríguez-Acosta: that when it was time to appoint their successors, they should choose ‘men with open spirits, capable of analysing suggestions without resentment or hostility, but with the prolific joy of wanting to share the miracle of life that we have the duty of making increasingly noble, beautiful and blessed’. This desire to acquire knowledge and share culture has lasted to present day. The foundation has grown in a variety of ways over the years, and in 2013 it was opened permanently to the public.

Since its creation, the foundation’s collections have grown with the addition of various museum, bibliography and document bequests, including items from Manuel Gómez-Moreno, a historian and archaeologist from Granada; Manuel Maldonado Rodríguez, a painter from Granada; and José Martínez Rioboo, an engineer and photographer closely linked to Granada’s cultural resurgence in the 20th century. However, tourists and many locals were unaware of the carmen for many years.

The institution is making a major informative effort in the form of an educational programme aimed at sharing its vast legacy so ‘visitors may become immersed in a full sensory and intellectual experience.’ As a result, the Rodríguez-Acosta Foundation hosts school field trips, family tours and children’s workshops almost daily.