Süleymaniye Mosque presides over the tallest of the seven hills of Istanbul, much like its instigator Suleiman the Magnificent has presided over the memory of the Ottomans and Western imagination. He was, undoubtedly, the sultan that history has remembered as the most successful, the best example of a dynasty of sultans dedicated to their work, concerned as much with wars as they were with the law, art and business.

After the Fall of Constantinople, when the Ottomans built Topkapi Palace, the former Byzantine palace became obsolete. Later on, Suleiman decided to build his own great monument to Islam, hiring the best architect and engineer of the time, Mimar Sinan. He took the project so seriously that he slept inside Süleymaniye Mosque for part of the duration of the construction work. His mission was downright ambitious: to outdo the Hagia Sophia and, especially, its magnificent dome.

To build Süleymaniye Mosque 3,500 workmen, craftsmen and foremen were deployed, working around the clock between 1550 and 1558. Today the mosque is surrounded by parks and gardens that extend its magnificence outdoors, forming an unparalleled setting. The complex, or külliye, also houses a hospital, a school, four madrasas or Islamic schools, a medical college, a public kitchen and the mausoleum of Suleiman and his wife, the legendary Roxelana.

Süleymaniye Mosque: testimony to triumph

Süleymaniye Mosque commemorates one of the crowning moments of Islamic culture across the world. Through Suleiman, who had extended his control through the Balkans and Hungary, even laying siege to Vienna, the Ottoman Empire was at the height of its expansion. This crowning point would come to its end, however, upon his death, before the empire eventually stabilised and began successive reforms.

Suleiman, or Suleiman the Magnificent, not only set foot in the heart of Europe but also extended his control through Africa and Asia. He was also a poet, patron, statesman and reformist. Suleiman led naval campaigns against the Portuguese and pursued their galleys throughout Africa and Asia. In the West, his name provoked both terror and admiration, while in the East, he took it upon himself to revitalise art, poetry and architecture.

All that remained was to build his own temple in old Constantinople, between two continents. To build Süleymaniye Mosque he commissioned the finest architect at the time, the legendary Mimar Sinan, for he was able to unite and harmonise Byzantine influence and Arab and Ottoman traditions. He designed grandiose buildings, brimming with luxury and open spaces that played with light and the echo of the walls. In this case, it was also proposed that the grandeur of the Hagia Sophia’s central dome be matched, without having to use pillars or any type of support that would spoil the visual purity of the sacred space.

Construction, which lasted from 1550 to 1558, was affected by Istanbul’s Great Fire of 1660, which went on for two days and destroyed a large part of the city, in addition to the earthquake of 1766. Moreover, during the First World War, Süleymaniye Mosque was used to store arms, an error that became evident when one of the ammunition storerooms exploded damaging a substantial part of the structure. The mosque was not fully repaired until 1956 when it was able to once again shine like it did in its initial glory days.

What to see inside Süleymaniye Mosque

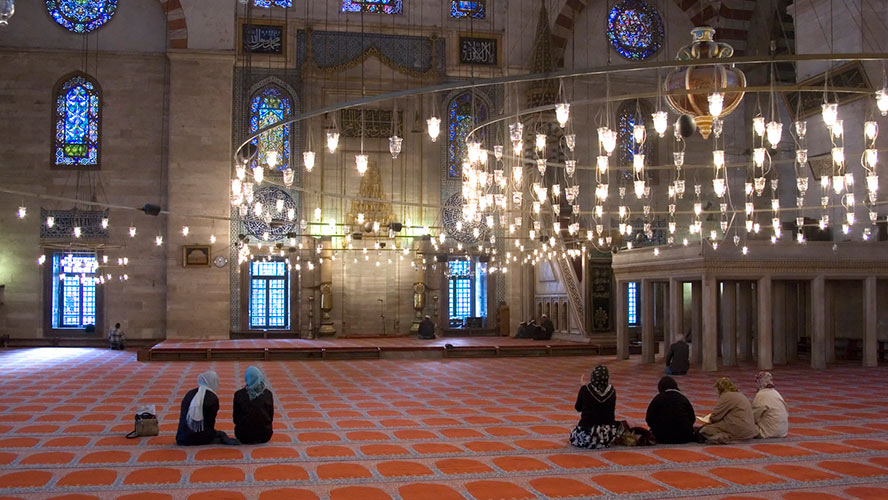

With its sheer size, Süleymaniye Mosque, designed by Mimar Sinan, could not help but represent the grandeur and prosperity of the empire. To decorate the interior, Sinan opted, among others, for Iznik tiles (Nicea), which, half a century later, would give the Blue Mosque (internal link) its distinctive colour. Inside the mosque there are also over 100 stained glass windows in different sizes and shapes, which illuminate the building playing with light and shadow.

Oddly enough, it can sometimes feel cool in the interior of Süleymaniye Mosque due to its design. An air flow system within the mosque directs soot from the lamps and candles to a single point, from where it was then collected and used to make ink. The echo of footsteps also rise up to the top of the vaulted ceilings in this vast open space. The magnificent central dome, almost as colossal as that of the Hagia Sophia, is flanked by semi-domes supporting its enormous weight. In total, it spans 53 metres in height and 26 metres in diameter, all of which is decorated with geometric patterns and plant motifs. Moreover, the dome’s counterweights are fitted against the walls, thus leaving the space open to view.

The inside of Süleymaniye Mosque also houses the marble mihrab, which indicates the direction of Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying, decorated with Iznik tiles. Like the pulpit, or mimbar, it has marble and mother of pearl inlay, in addition to gemstones such as turquoise, representing flowers and other motifs. The floors are covered in various rugs, one of which is a persimmon colour and was brought from Cairo. At the top, as in Istanbul’s finest mosques, the vaults are covered with brightly-coloured calligraphic, floral and geometric designs, which direct your gaze up towards the oculus of the central dome where the sunlight enters.

The courtyard of Süleymaniye Mosque

Be sure to take some time to admire the mosque’s courtyard, as it is absolutely magnificent. Spanning almost 20,000 square metres, in it you can start to get a feel for the monumental nature of the interior.

Tomb of the sultans

Behind the mihrab wall of Süleymaniye Mosque are the mausoleums of Suleiman and his wife, Hürrem Sultan or, as she is known in the West, Roxelana, Like the Valide Sultans who were responsible for the construction of the New Mosque, she would be an even more prominent figure of what is known as the Sultanate of Women, a period spanning almost a century in which the women closest to the sultan of the Ottoman Empire exerted great power and patronised the arts, among other things.

Born in Poland and of Christian origin, Hürrem Sultan was captured by Crimean Tatars during a raid and sold to the far-off court of the Ottoman sultan. Over time, Hürrem, who entered the Imperial harem, would become Suleiman’s favourite. Breaking with Ottoman tradition, he did not hesitate to marry Hürrem, who was a Muslim convert of Christian origin. As Imperial Consort, she had an influential role in the decisions of the state and diplomacy, in addition to carrying out a large amount of charitable work, building all kinds of buildings and patronising the arts in the empire.

In Europe she was known as Roxelana because of her red hair, and she would go on to become a legendary figure due to her Christian origins, her incredible rise and her capacity for diplomacy and government. Her name, Hürrem, means ‘the cheerful one’.

Hürrem’s octagonal-shaped mausoleum dates from 1558, the year of her death. Its interior is covered with Iznik tiles and eight delicately-decorated mihrab-like niches are carved out of the wall. If the outside stands out for its simplicity and elegance, the inside contains a series of highly-refined mosaics.

The tomb of Suleiman is even more magnificent. It is decorated with ivory, precious metals, marble, tiles and, in particular, a very special stone. Supposedly, one of the stones embedded in one of the arches was part of the Black Stone of Mecca. From the outside the portico building supported by 24 columns is crowned by an elegant dome with beautiful lattice windows beneath its pointed arches. The Iznik tiles used in its decoration are the earliest tiles to feature the turquoise colour for which they would become known in the Blue Mosque. The mausoleum of Süleymaniye Mosque also houses the remains of the couple’s daughter, the beautiful Mihrimah Sultan, as well as the sultans Suleiman II and Ahmed II.